Multimodal contrastive learning for brain-machine fusion

We proposed a brain-machine fusion approach to achieve the brain-in-the-loop modeling and brain-out-of-the-loop application.

Introduction

Harnessing the complementarity between the brain and artificial neural networks has shown great promise for the development of novel brain-machine fusion systems that may rival the robustness and flexibility of the human visual system. Nonetheless, due to the requirement of human involvement, brain-machine fusion models are challenging to apply in a brain-in-the-loop manner to handle task demands that involve long duration, high intensity and complex operating environments. To tackle this problem, we proposed a brain-machine fusion approach to achieve the brain-in-the-loop modeling and brain-out-of-the-loop application. The similarities and differences between the image representations of brain responses and image features computed by deep convolutional neural network (DCNN) are firstly analyzed using a rhesus monkey dataset, and the results lay the foundation for the feasibility of brain-machine fusion. A brain-machine fusion model is then developed and a multimodal supervised contrastive learning method is proposed to jointly learn the image representations for brain responses and DCNNs. The fusion model can be applied in a brain-out-of-the-loop manner, effectively addressing the challenges encountered by human-involved approaches. Extensive experiments on a self-built human vehicle detection dataset demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method in improving the generalization ability of the downstream image classifiers, both in cross-modal learning or multimodal fusion settings.

Contributions

We investigated the similarities and differences between the image representations of brain responses and image features computed by DCNNs using a rhesus monkey dataset, demonstrating that there are complementarities between the two, and thus there is a potential to improve the system performance through information fusion.

We developed a brain-machine information fusion model with a siamese network architecture and propose a multimodal supervised contrastive learning method to jointly learn the image representations for the brain responses and DCNNs, which not only improves the generalization ability of the downstream image classifier, but also enables it to be applied in a brain-out-of-the-loop manner.

The proposed brain-machine fusion method was validated on a self-built human vehicle detection dataset through extensive cross-subject and cross-task analyses. Its effectiveness demonstrates the feasibility and potential of brain-out-of-the-loop application of the brain-machine fusion models.

Datasets

Two datasets were used in this study. A rhesus monkey dataset was used for complementary analysis between the brain responses and the DCNN image features, and a self-built human vehicle detection dataset was used for brain-image fusion modeling and application in real scenarios.

Rhesus monkey dataset

The rhesus monkey dataset is obtained from the Brain-Score platform including both the stimulus images and EEG brain responses. The stimulus images were synthesised artificially by overlapping the two-dimensional (2D) projections of three-dimensional (3D) objects on random backgrounds. There are 8 object categories, where each category contains 8 subcategories, 50 images per subcategory, for a total of 3200 images. The EEG brain responses were collected from the visual cortex ventral stream region of two trained adult rhesus monkeys, by implanting 168 and 128 (publicly available data only 88) electrodes in the inferior temporal lobe (IT) and V4, respectively. For brain responses acquisition, groups of 5-10 stimulus images were presented sequentially with each image presenting for 100 ms, followed by a 100 ms blank to keep the monkeys focused. Each stimulus image was presented at least 28 times, with an average of 50 times. The publicly available brain responses from the Brain-Score platform were averaged in both the dimension of image presentation times and brain responses time for 70-170 ms after presentation. Thus, the EEG brain responses of IT and V4 are 168- and 88-dimensional vectors respectively, in which each vector element represents the averaged brain response intensity of an electrode.

Self-built human vehicle detection dataset

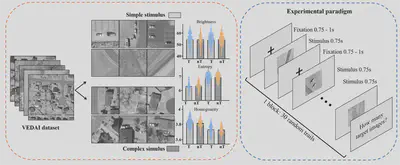

Visual stimulus images for the vehicle detection experiment were collected from the VEDAI dataset in the publicly available Utah AGRC database. In order to exclude the influence of color, we only used large-size (1,024 × 1,024 pixel$^{2}$) infrared image in this study. From the infrared images, we manually cropped patches containing at least two vehicles and of similar size. Totally 2,030 patches (1,015 target patches and 1,015 non-target patches) were obtained, and then resized to 300 ×300 pixel$^{2}$. Considering that the patches were designed to be viewed by human subjects, the scene complexity was first visually inspected based on the type, number, distribution, and similarity of background items. Patches with high confidence were assigned to the simple or complex group, while other indistinguishable patches were excluded. Thereafter, quantitative evaluation in terms of brightness and scene complexity was performed for each patch. The brightness was measured as the average intensity, and the scene complexity was measured by information entropy and gray-level homogeneity indices. Outliers exceeding 1.5 times the interquartile range of these measure were sequentially excluded from the stimulus set.

The above screening procedure eventually yielded 1800 patches, including 450 patches of each of the four types: simple scene with vehicle (simple-scene target), simple scene without vehicle (simple-scene non-target), complex scene with vehicle (complex-scene target), and complex scene without vehicle (complex-scene non-target).

The experiment comprised two vehicle detection tasks respectively in simple scene and complex scene, totally lasted two hours including preparation work. During the experiment, the participants were cued to perform a practicing block to adapt to the experimental environment and familiar with the experimental process before the experiment officially began. For each of the two tasks, 900 visual stimulus images containing two categories (450 targets and 450 non-targets) were partitioned into 30 sets of 30 images each for block design. In one block, the set of 30 images contained approximately 40% to 60% target images and were randomly permuted. The order of the blocks was also randomly permuted. The participants were asked to fully focus on vehicle detection when the monitor flashed the images of each stimulus for a period of 0.75 second during each block. A black crosshair was displayed in the center of the monitor for 0.75–1 second as the inter-stimulus interval between two adjacent images. At the end of each block, the participants made keystroke judgments about the number of target patches in the block.

We acquired continuous EEG data using an ActiCHamp EEG system supplied by the Brain Products Company. Sixty-four channels including one reference channel (channel Iz) were positioned on the head according to the international standard 10-10 system. The EEG data were sampled at a rate of 1,000 Hz and the impedance of each electrode was kept below 5 k$\Omega$ prior to the beginning of recording. The raw EEG data were preprocessed offline in MATLAB using the EEGLAB toolbox (version 13.6.5b).

Fig. 1. Left: the generation of stimulus set and statistical results between targets (T) and non-target (nT) stimuli in simple and complex scene groups. Right: the temporal structure of stimulus presentation. Both simple and complex stimulus task shared the same experimental procedure.

Complementarity between brain and DCNN

Methods

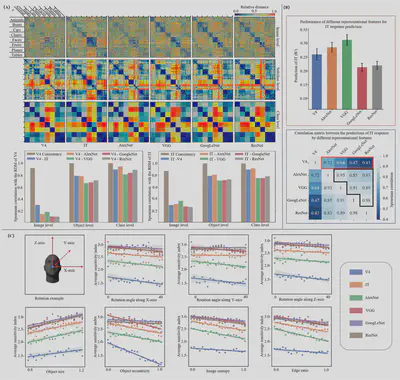

The rhesus monkey dataset was used for complementary analysis between the brain responses and the DCNN image features. We employed the representational similarity analysis (RSA) method to analyze the similarity between the brain responses and the DCNN features. The basis of RSA is the representational dissimilarity matrices (RDMs), and we calculated the RDMs for brain responses and DCNN features separately using the Euclidean distance. Specifically, the RDMs were calculated from three levels of granularity, including the image level (RDM shape of 3200 × 3200), the object (subclass) level (RDM shape of 64 × 64), and the class level (RDM shape of 8 × 8). The similarities between the RDMs were then evaluated using Spearman’s correlation, and the retest consistency of brain responses between the multiple presentations of the same stimulus image at different levels was used as the noise-limited upper bound.

To investigate the capacity of DCNN features to fit the brain responses, the partial least squares (PLS) was used to predict the brain responses of individual electrodes from the image features.

To investigate whether the differences in the image representations of brain responses and DCNN features are related to image complexity, we used the classification sensitivity index ($d^{’}$) in Rajalingham et. al. (Journal of Neuroscience 38(33), 2018) to estimate the sample separability in different feature spaces. The higher the sensitivity index, the better the separability. The sensitivity indices of the brain responses and DCNN features for each stimulus image were computed separately.

Fig. 2. Complementarity analysis between the image representations of brain responses and DCNNs. (A) Visualization of RDMs at different levels of classification granularity, and similarity between the RDMs of the brain responses and the DCNN image features. V4 Consistency and IT Consistency represent the retest consistencies of V4 and IT brain responses, respectively. (B) Fitting ability of V4 brain responses and DCNN features to predict the IT responses. (C) Effects of object and scene complexity on classification performance (averaged sensitivity indices) of the brain responses and DCNN features for all stimulus images.

Results

We found that the brain responses in the primate ventral visual pathway and the DCNN-based visual features show high similarity at the object and class levels, while significant differences existed at the image level. This is consistent with previous behavioural previous studies on DCNN and primate image classification, in which they found that DCNN could accurately predict the primate’s classification patterns at the object level, but hardly at the image level. It can therefore be inferred that the DCNN models can be compared to primate vision at coarse-grained object level and class level, but cannot fully account for the fine-grained image-level representations. When using the V4 responses and DCNN features to predict the IT responses, our results indicated that the shallow DCNNs (AlexNet and VGG) could capture more information about IT responses than the deeper DCNNs (GoogLeNet and ResNet), but neither V4 nor various DCNNs could fully represent the IT brain responses. Furthermore, we found that V4 response and DCNN features captured different aspects of IT response information, while all DCNN features mostly captured the similar aspects. These results suggest that DCNN features cannot fully account for the image representation information of the brain responses, but encode the high-level semantic information of the image in a different way. This complementary between DCNN and brain representations highlights the promising potential and practical value of constructing brain-machine fusion models.

Notably, we found that the shallow DCNNs are better at capturing the IT response information than the deeper models, contrary to the previous behavioural study. This inconsistency can be explained in two ways: (1) The localized brain responses of the IT region do not fully reflect the information processing in which multiple regions of the brain are involved. (2) The lack of temporal information in the IT response data cannot reflect the dynamic process of visual processing on time scales and may reduce the brain’s representational capacity. Due to the above limitations, the brain responses in the rhesus monkey dataset can only partially reflect the object recognition ability in primates, which is insufficient to form a complete semantic representation of the stimulus images.

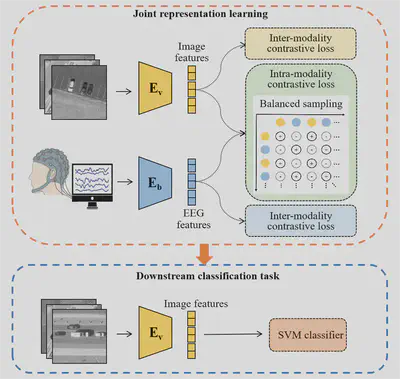

Brain-machine fusion model

To explore the cross-modal complementarity between brain responses and DCNN features, we proposed a brain-machine information fusion model. The fusion model adopts a siamese network architecture to incorporate brain responses into the feature learning phase, which is pre-trained using the supervised contrastive learning strategy to learn the structured joint embeddings between the brain responses and DCNN features. After training, the fusion model can be applied to the downstream classification tasks in multimodal fusion setting or unimodal setting. The later enables the brain-out-of-the-loop application of the fusion model.

Fig. 3. Schematic diagram of the proposed brain-machine information fusion method

The fusion model employs two encoders to project the EEG data and stimulus images into a common embedding space. The EEG encoder adopts the EEGNet architecture by replacing its softmax classification layer with a linear layer that projects the learnt features into a one-dimensional feature vector. The image encoder is constructed using the DCNN models including the AlexNet, VGG, GoogLeNet, and ResNet, respectively, with the output layer replaced by a linear layer, i.e., the linear probes of the DCNN models.

Considering the presence of labels in our data, the EEG and image encoders are trained using the supervised contrastive learning strategy. Since our optimization goal is to learn the joint optimal representation of EEG and images in a common embedding space, we design a contrast loss function with three components: an inter-modality loss and two intra-modality losses.

After training the EEG and image encoders, they can be used as feature extractors in the downstream tasks for either multimodal or unimodal classification. In the former, the EEG and image features are combined to train a classifier to classify the stimulus images. However, the multimodal fusion setting can only be applied when brain responses are also available, which is difficult to collect in many real-world scenarios, especially in real-time tasks. Benefiting from the siamese network structure that provides the embedded EEG and image features separately, our brain-machine fusion model can be applied in situations where only the image inputs are available, i.e., in the cross-modal learning setting. Although the brain is not in the loop, the prior information of the brain response has been captured by joint representation learning in the pre-training stage and reflected in the embedded image features.

The advantages of the proposed brain-machine fusion method were evaluated through three image classification experiments on the vehicle detection dataset. Given the high variance in EEG data among the subjects, we trained the models for individual subjects. For each of the two detection tasks (simple scene and complex scene), each subject’s data was randomly partitioned into five folds, each containing the same number of samples from each group (targets and non-targets). For a given learning setting, the downstream classification performance on individual subject’s data was measured by the five-fold cross-validation accuracy, and the mean accuracy of all subjects was used as the overall performance.

Results of brain-machine fusion model

We first compared the image classification performance of different learning settings including single-modal learning, cross-modal learning, and multimodal fusion. In the single-modal learning setting, only one modality (EEG or image) of data was used in the feature learning and downstream classification (SVM classifier training and testing) phases. In the cross-modal learning setting, both the EEG and image data were used to train the brain-machine fusion model, but only the EEG or image data was used in the classification phase. This setting, when only using the jointly learnt image features for classifier training and testing, is what we call brain-in-the-loop modelling, brain-out-of-the-loop application. In the multimodal fusion setting, both the EEG and image data were used in all the learning phases.

From the experimental results, we can draw the following conclusions for both the simple and complex scene tasks. Firstly, the image data is easier to classify than the EEG data when only single-modal data is used. Despite the structural differences between the EEG model (EEGNet) and the image model (ResNet), there are more reasons to believe that the inferior discriminative ability of the EEG data is due to its inherently low signal-to-noise ratio and non-stationarity. Second, by using the joint brain-image representation learning, the downstream classification performance in the cross-modal settings are significantly improved over its single-modal learning counterparts. This again demonstrates the existence of complementarity between the brain responses and DCNN features, and that this complementarity can be captured by multimodal contrastive learning. Third, the best classification performance is achieved with the multimodal fusion setting, but as mentioned above, the full brain-in-the-loop approach is difficult to apply in real-world scenarios.

The second experiment tested whether the brain-image joint representation learning could improve the cross-subject generalization of the EEG data. Specifically, each subject’s model was tested on other subjects’ data and then averaged to evaluate the model’s generalization performance. We employed two settings for cross-subject analysis: zero-shot transfer and full-shot transfer. Compared to the counterpart results, the accuracy of cross-subject testing is significantly decreased, indicating the large variations in the EEG data between the subjects. The performance of full-shot transfer is better than that of zero-shot transfer. This is mainly attributed to the fact that the training and test data of the SVM classifiers come from the same subjects in the case of full-shot transfer, whereas the training and test data are from different subjects in the case of zero-shot transfer. In both cases, the EEG features obtained using joint representation learning significantly improve the performance of cross-subject classification, demonstrating that brain-machine fusion yields a better representation of the EEG data.

The third experiment tested whether the brain-image joint representation learning could improve the cross-task generalization of the DCNN image representations, where the image representations and the SVM classifiers trained on the simple scene images were tested on the complex scene images, and vise versa. Similar to the learning settings in the second experiment, we conducted the zero-shot and full-shot transfer experiments. From the results, similar conclusions can be drawn as in above experiments. The image features jointly learnt with the brain responses can better decode the object information than that learnt from the image data alone. More importantly, our results demonstrate the practicability of brain-in-the-loop modeling and brain-out-of-the-loop application. The elimination of the need for brain data in model testing greatly broadens the application scenarios of the models.

Conclusion

We have proposed a brain-machine fusion method for object classification that exploits the complementary nature between image representations of the brain and DCNN. We developed a multimodal supervised contrastive learning model to jointly learn the brain and DCNN representations of the images, which significantly improves the generalization ability of the downstream classifiers. Most importantly, the proposed brain-machine fusion model is able to be applied in a brain-out-of-the-loop manner due to the adoption of a siamese network architecture, thus overcoming the difficulties faced by the human-involved brain-in-the-loop approaches. Our brain-out-of-the-loop strategy can maximize the automation advantages of brain-machine fusion models and broaden their application scenarios. The results are significant for the research and design of brain-machine information fusion systems, and provide new ideas for the cross-study of computer vision and cognitive science.

This work has been publised in Information Fusion:

Shilan Quan, Jianpu Yan, Kaitai Guo, Yang Zheng, Minghao Dong, Jimin Liang*, Multimodal contrastive learning for brain-machine fusion: from brain-in-the-loop modeling to brain-out-of-the-loop application, Information Fusion, vol. 110, 102447, 2024. IF: 18.6